Why is the Conservation and Protection of Northern Wild Rice (Zizania palustris) So Important?

From:https://www.nbs.net/articles/5-main-threats-to-biodiversity

The rapid decline of biodiversity among the planet’s numerous plant species is being lost at unprecedented rates all over the world.

Unfortunately, the story of northern wild rice is no different and declines have been widely documented across the Great Lakes Regions of the United States.

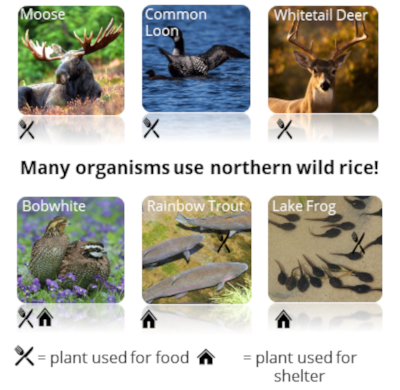

Northern wild rice is an important constituent to Upper Midwest aquatic ecosystems. The species provides food and habitat for a wide range of species.

The high protein content and nutritional quality of NWR, along with high seed production rates make it a valuable resource to birds during breeding and migration. NWR has been rated one of the top ten constituents in the diet of several duck species. At least five duck species (mallard, ringneck, pintail, blue-wing teal, and green-wing teal) and more than 35 shorebirds and wading bird species use wild rice for resting, foraging, nesting, or raising broods.

A 2008 report from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources identified several contributors to the decline of northern wild rice in Minnesota. Changing water levels from human management of our lakes as well as recreational activity and shoreline development on our lakes are two major contributors as is resorts on the water. Pollutants and climate change are also problems for wild rice. A 2018 study2 from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency documented how sulfate pollutants in our Minnesota waterways are negatively affecting northern wild rice stands.

https://passionpassport.com/anishinaabe-northeastern-ontario-first-nation/

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/climate-change-threatens-the-ancient-wild-rice-traditions-of-the-ojibwe/

https://wisconsinlife.org/story/wild-rice-harvest-tradition-passed-down-to-youth/

Culturally, NWR is considered a sacred food to Anishinaabe, including Ojibwe and Potawatomi Tribes, and Dakota peoples living in the Great Lake region of the United States and Canada. Known as ‘Manoomin’ to Anishinaabe and ‘Psiŋ’ to Dakota, NWR has been hand-harvested by these First Peoples for centuries using a canoe and two wooden poles known as rice knocker. Today, individual bands of Anishinaabe and Dakota in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Canada still hand-harvest NWR. To learn more, it is important to identify resources created and led by Anishinaabe and Dakota First Peoples. Here are a few resources that we have found to be helpful:

What is Our Program Trying to Do to Help?

Genetic Diversity Assessments: Genetic diversity is the cornerstone of a species survival as it provides a species with the ability to adapt to environmental changes. For northern wild rice, the species is being inundated with changes to its habitat in a very rapid way evolutionarily speaking, which is likely eroding genetic diversity. Assessing the genetic diversity of northern wild rice in Minnesota is extremely important to trying to conserve the species. Once current levels of genetic diversity are known, those levels can then be monitored to ensure they don't drop dramatically. If we see that diversity levels are dropping rapidly, then we can go after the source of the problem. There is no way to assess how much diversity has already been lost during the species decline but we can work to preserve what is still there.

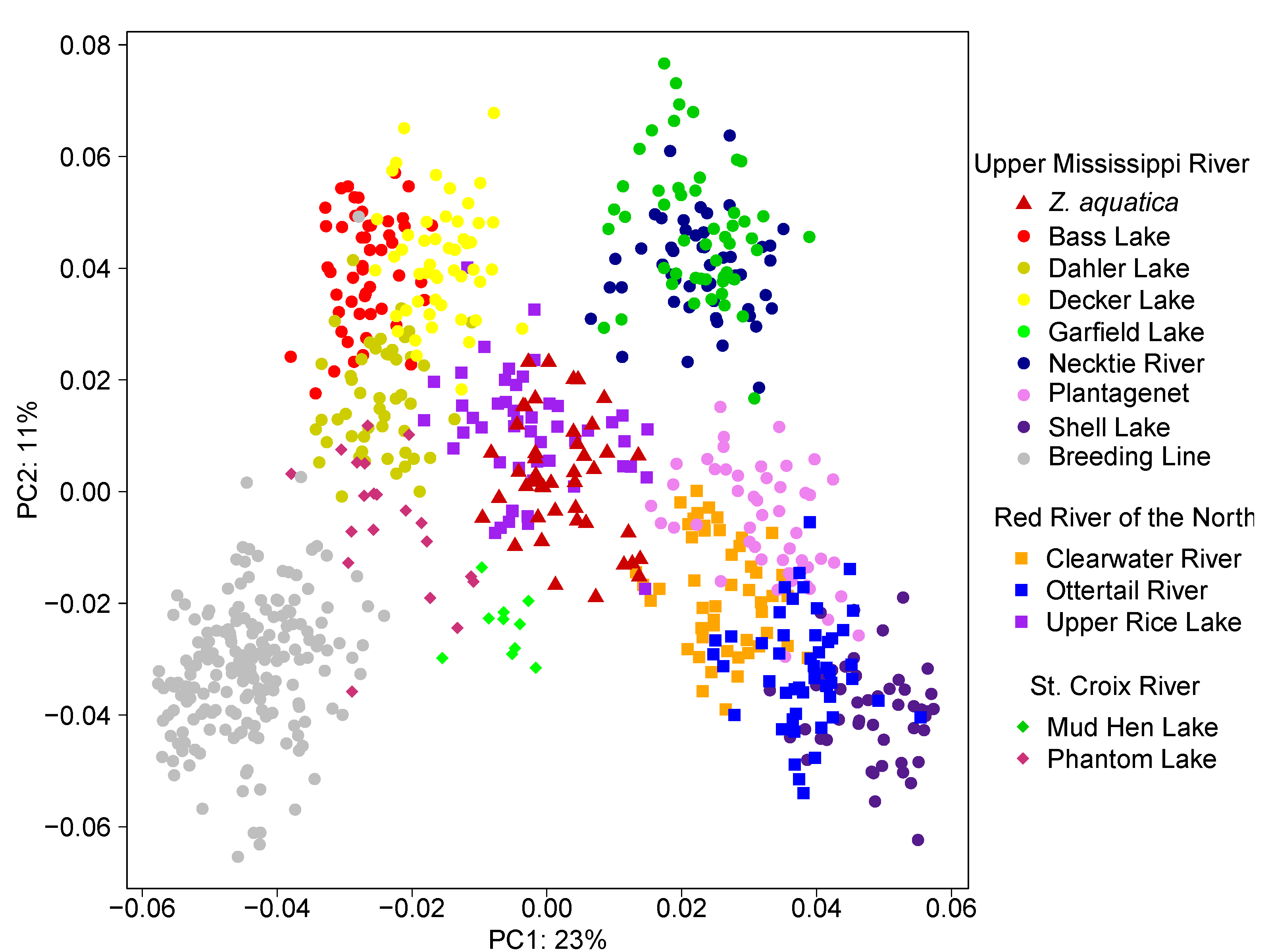

The figure above is a Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCA) plot of individual northern wild rice plants from 12 lake and river populations collected across Minnesota and Western Wisconsin in 2018 from three different HUC-8 watersheds. Each dot represents one individual northern wild rice plant. Briefly, a 3 inch leaf was collected from each plant and genotyped using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

Individual populations cluster closely together, representing the similarity of individuals within lakes – also known as ecotypes. Larger grouping patterns by watershed can be seen as well.

This figure highlights the limited gene flow between individual wild populations as well as the importance of each individual population and its contribution to the overall genetic diversity found within the species.

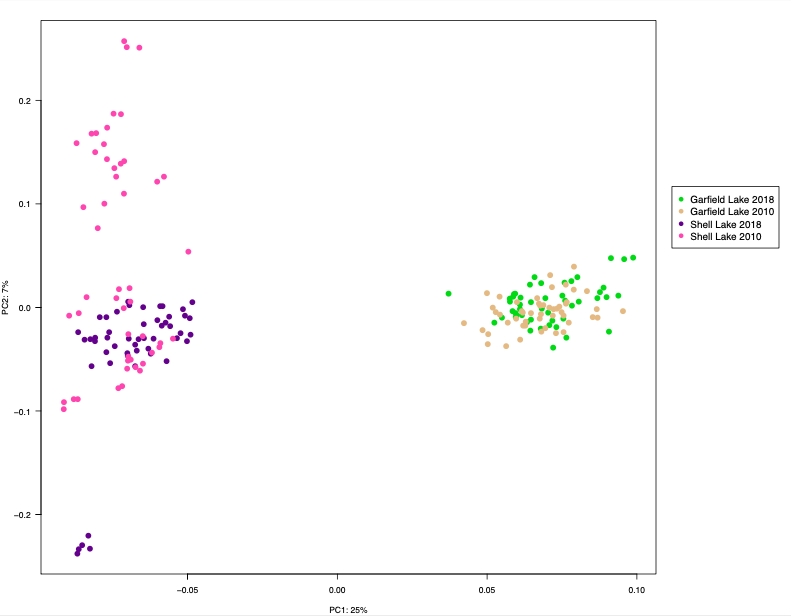

Spatio-Temporal Genetic Diversity Assessments: While genetic diversity assessments, like the one we present above, are important in understanding the breadth of genetic diversity and adaptability of northern wild rice, both as a species as well as individual populations, assessing changes in genetic diversity over both space and time provides more information.

(Haas et al., 2022, in preparation)

In this figure, we present a spatio-temporal genetic diversity analysis of two lake populations of northern wild rice collected in 2010 and in 2018.

We see that over time, the population in Garfield Lake has not seen a reduction of genetic diversity, while Shell Lake has (the pink dots at the top left of the plot).

This data suggest that over the span of 8 years, something has negatively impacted the northern wild rice population of Shell Lake. Continued efforts to understand what are the drivers of this change is important for conservation efforts.

Gene Flow Studies:

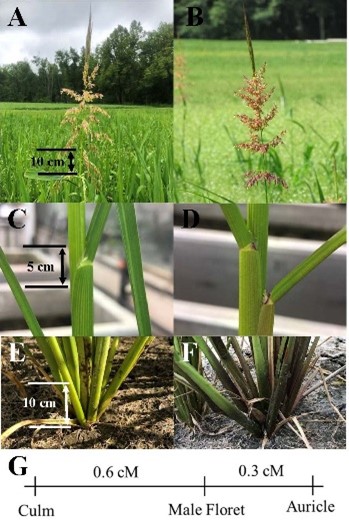

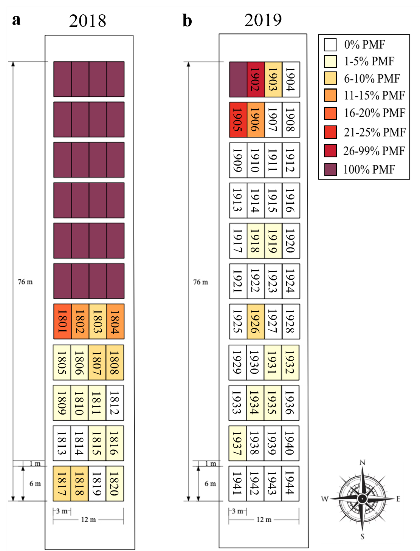

Pollen-Mediated Gene Flow. We have started to undertake studies to evaluate the potential spread of pollen, using a population with recessive white male florets. This allows pollen flow to be tracked by floret color, greatly simplifying the collection of the data. Studies conducted in 2018 and 2019 revealed that the primary pollen-mediated gene flow occurred within the first 7 m from the donor source, with no gene flow detected past 63 m. This is a good indication that pollen does not travel as far as previously thought. However, we need to follow up on these studies. Interested to learn more? Read the publication here!

Why was the Cregan 2004 Study an Inadequate Evaluation of Pollen-Mediated Gene Flow in Northern Wild Rice?

A 2004 study using the bottlebrush trait, a bunched male flower structure, to track pollen travel reported that wild rice pollen can travel many kilometers.

The bottlebrush trait is linked to male sterility = plants don’t produce pollen. Any seed that develop on these plants should indicate pollen that came from non-bottlebrush plants.

However, the link between the bottlebrush trait and male sterility is often broken in some plants, which means pollen is available for fertilization (right picture).

Seed Banks and Seed Storage:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/croptrust/3851518425

Around the world there are seed banks and vaults that store thousands of different plants species to protect and conserve their genetic diversity. Currently, northern wild rice is not saved in any of these seed banks because the seed is very difficult to store. To learn more about what the program is doing to learn more about northern wild rice seed and how we can store it effectively to get the species saved and protected in seed banks, go to our Seed Storage Research Page.

The fact that northern wild rice cannot be stored outside its native habitat (ex-situ storage), emphasizes the importance of protecting northern wild rice lake and river populations across the species range (in-situ).

References

Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. 2008. Natural Wild Rice in Minnesota. https://files.dnr.state.mn.us/fish_wildlife/wildlife/shallowlakes/natural-wild-rice-in-minnesota.pdf

Gietzel, C., Duquette, J., McGilp, L., & Kimball, J. (2021). Evaluation of a Recessive Male Floret Color in Cultivated Northern Wild Rice (Zizania palustris L.) for Pollen-Mediated Gene Flow Studies. Crop Science, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20647